About Ebykr

Ebykr celebrates classic and vintage lightweight bicycles through provoking imagery and opinion. Let's roll together!

About Ebykr

Ebykr celebrates classic and vintage lightweight bicycles through provoking imagery and opinion. Let's roll together!

Cycles Automoto was a pioneering manufacturer of bicycles and motorcycles founded at the turn of the 20th century in Saint-Étienne, France. Well regarded for thoughtful design and meticulous construction, Automoto grew in popularity until merging with the Peugeot group in the early 1960s. Fancier Automoto bicycles—of which there certainly are some—are relatively hard to find these days and costly when available for sale.

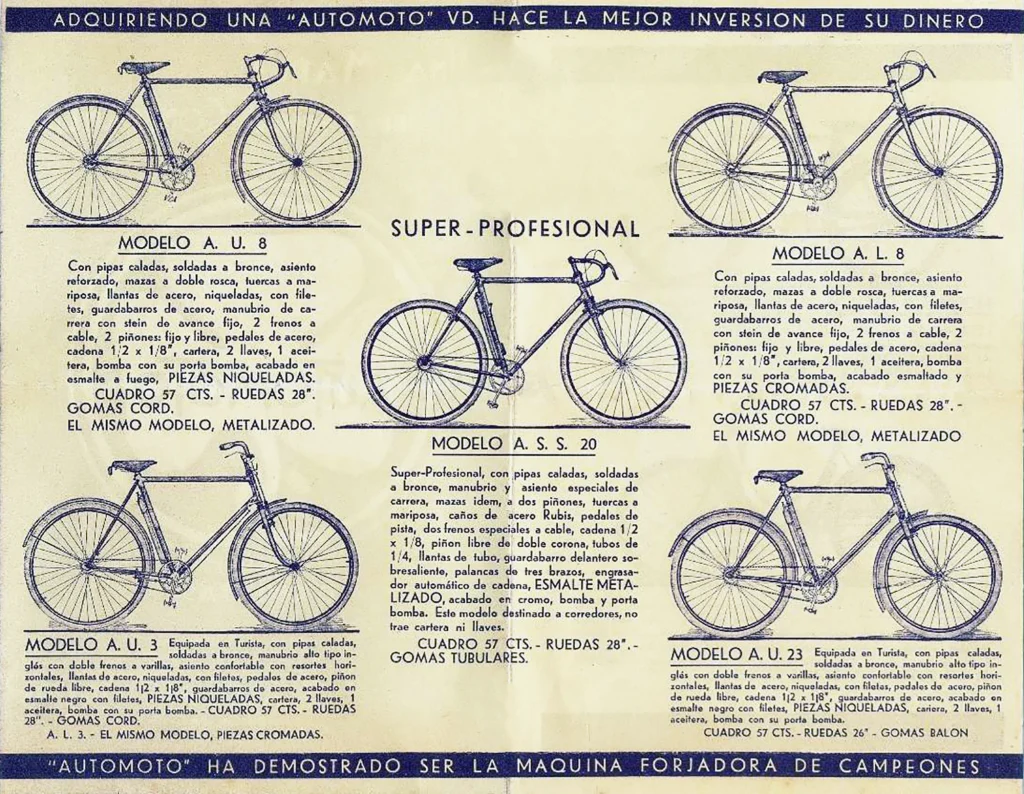

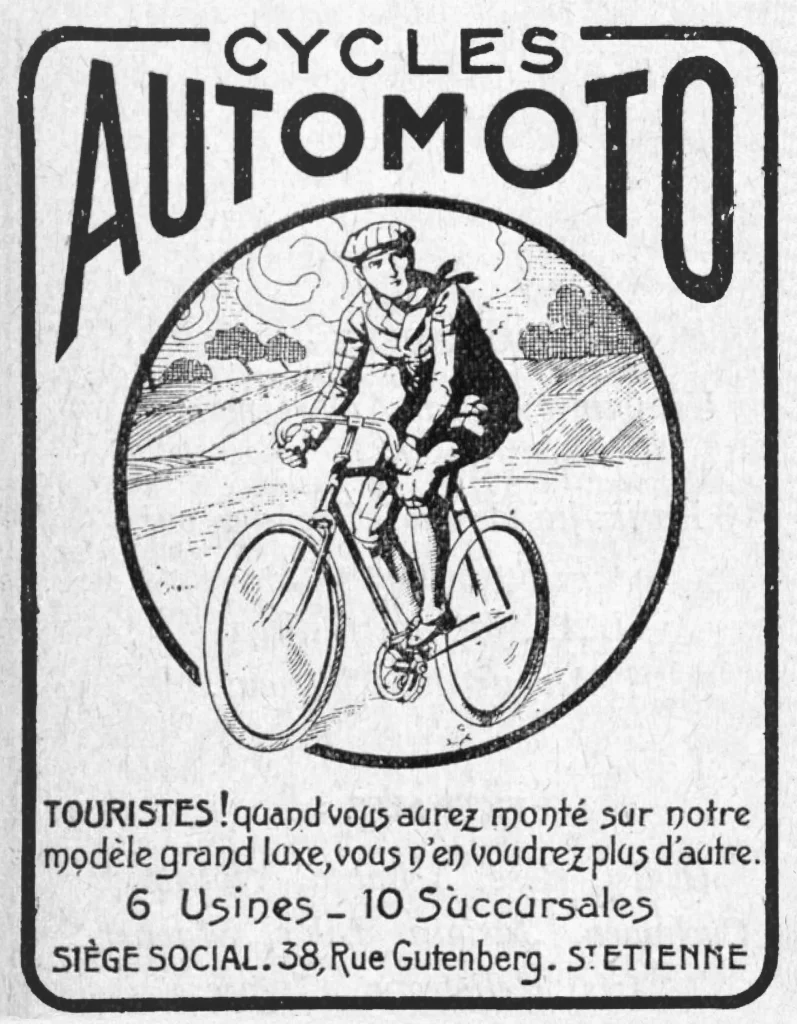

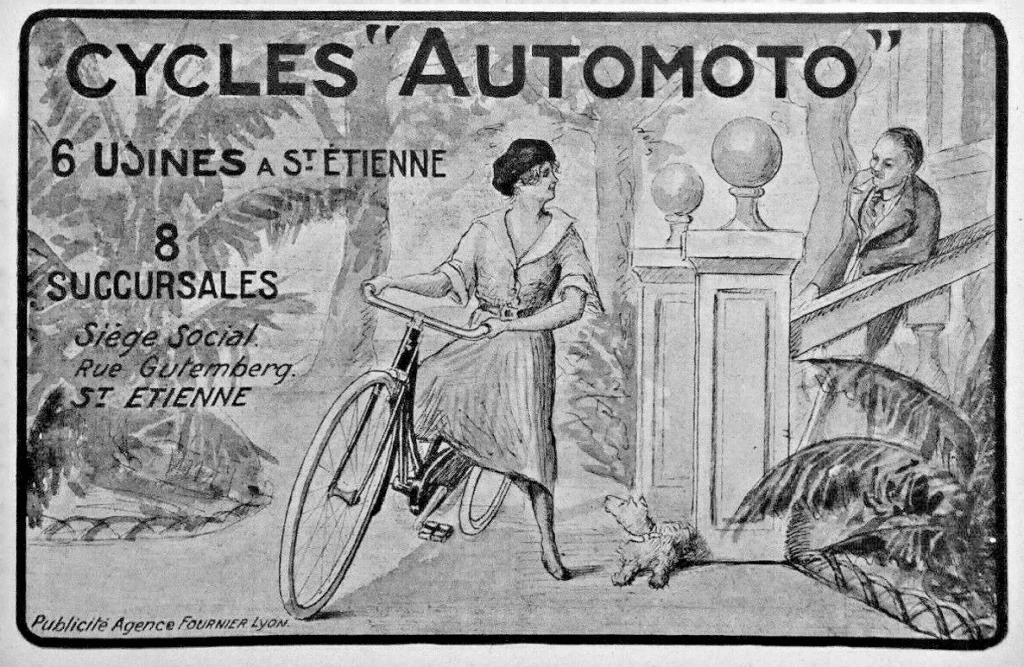

It wasn’t always that way. Part of Automoto’s popularity is attributable to the wide range of products historically available from the company, whose bicycle line alone grew to include a full twenty models at once. Another less immediate part of that popularity is traceable to the Automoto mystique, one whose allure—synonymous with a passion for quality—somehow continued growing through a pair of World Wars and burgeoning product availability in places like South America.

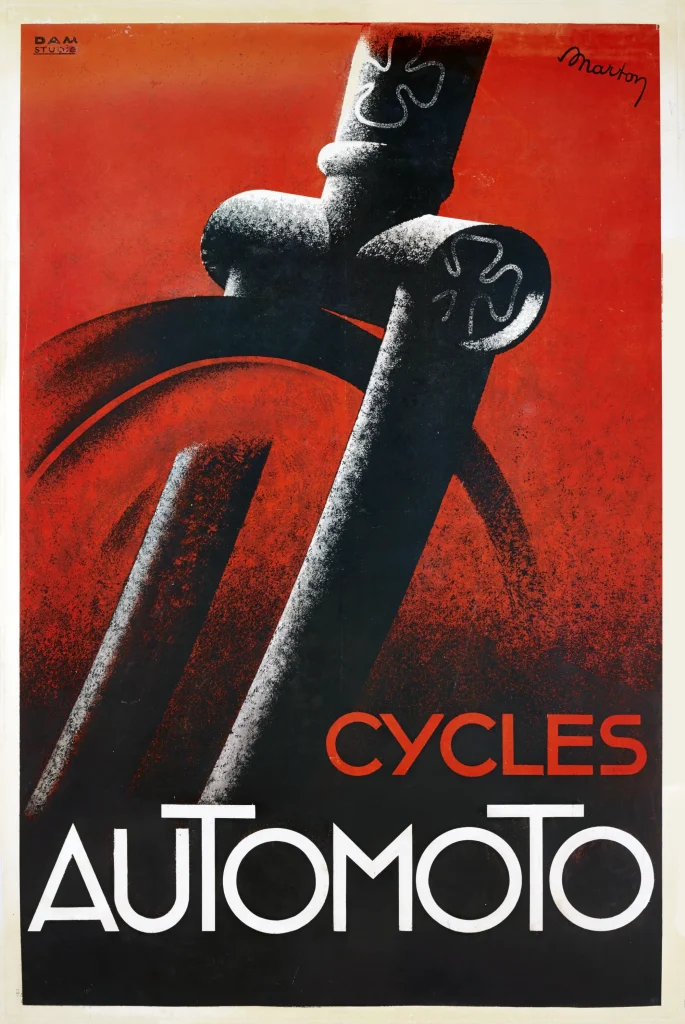

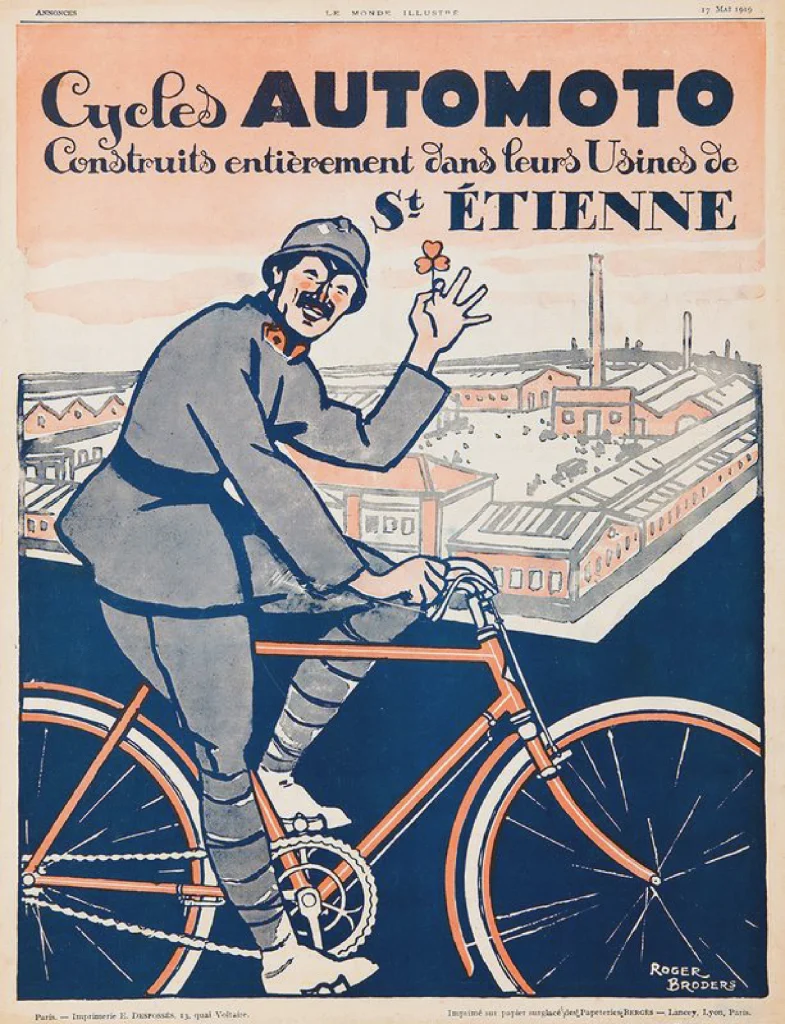

Today, more than a half-century after the final Automoto left its Saint-Étienne birthplace, the timelessness of the company’s cloverleaf logo and the transportation machinery that it produced in its compact fifty year existence remain as meaningful as ever. Maybe it’s those striking posters from the Belle Époque and Art Deco periods that have taken over the Internet. Whatever the reason, the marque lives on in our minds if not our daily lives.

One hundred years ago, things were very different. Taking a train from northerly Paris to southerly Saint-Étienne meant an uncomfortable and unreliable daylong journey through central France down into the Loire alpine range, southwest of Lyon. It also meant leaving arguably the world’s most culturally sophisticated city for among its most industrial minded.

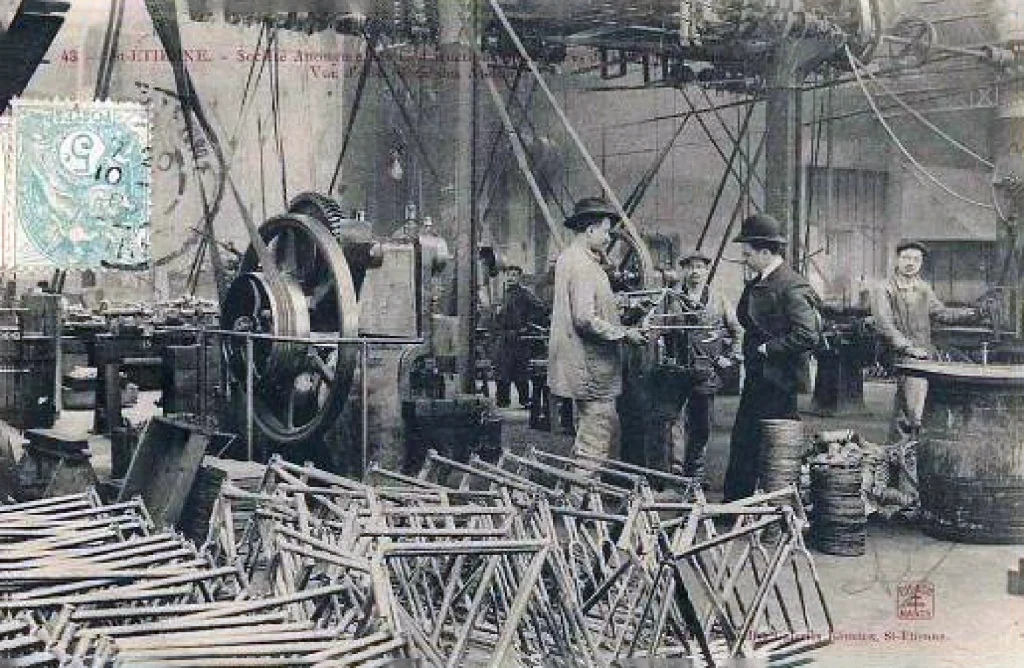

Unlike urban and chic Paris, St.-É’s, as locals sometimes call it, was ignominiously known for its mining operations and related industries. Inglorious as they were, these roots tapped deeply into abundant local iron and coal deposits, providing the essential elements necessary to seed and fuel what became known as the industrial revolution (or at least France’s contribution to it) and Automoto was squarely in the middle of things.

French cycling heritage—which is to say cycling heritage in general—originated in Saint-Étienne. Popularly referred to as the “cycling capital of France” by unbiased experts like Sheldon Brown and Saint-Étienne itself, the city gave rise to notable cycling companies like Manufrance/Mavic, Motobécane and Vitus. It also gave rise to notable cyclists like Paul de Vivie (Velocio), the father of French cyclo-touring and an early champion of the blessed rear derailleur.

Today, Saint-Étienne is recognized as a UNESCO “City of Design” and its amazing Museum of Art and Industry hosts the largest public collection of bicycles in France, from early bone shaker forerunners to contemporary carbon prototypes. What Coventry did for British advancements in cycling, Saint-Étienne mirrored for French advancements in cycling. And perhaps then some, in this author’s humble and respectful opinion.

The summer of 1889 brought together four businessmen from Saint-Étienne—Montet (or Louis) Chavanet, Claudius Gros, Pierre Lapertot and Messieur Pichard—who formed a professional society named the “Société de Constructions Mécaniques de Cycles et Automobiles.” These men shared a passion for unpowered and powered mechanical transportation devices, at the time meaning bicycles, tricycles and quadricycles, and desired a common forum to exchange ideas around them.

After nearly a decade of doing so together, all the while refining various designs and coalescing as a team, Gros, Pichard and another man named Messieur Goudefer registered the Automoto marque in 1898. Another business was then registered in 1899 under the name, “Société de Construction Mécanique de cycles et automobiles Chavanet, Gros, Pichard et Cie.” Perhaps Chavanet felt left out, to the apparent detriment of Goudefer.

The business was listed as a limited company in 1901 and renamed “Société Anonyme des Constructions Mécaniques de la Loire,” or CML for short. All involved must have breathed a great sigh of relief given the new, short acronym they could start referring to their company by. Not until another decade had passed that included a forced liquidation brought about by strategic missteps related to autobody manufacture did they assume their eventual name of Cycles Automoto in 1910. And so the three leaf clover was born, not so much with ambitions for growing into automobile manufacture as already having a healthy skepticism of all it entails.

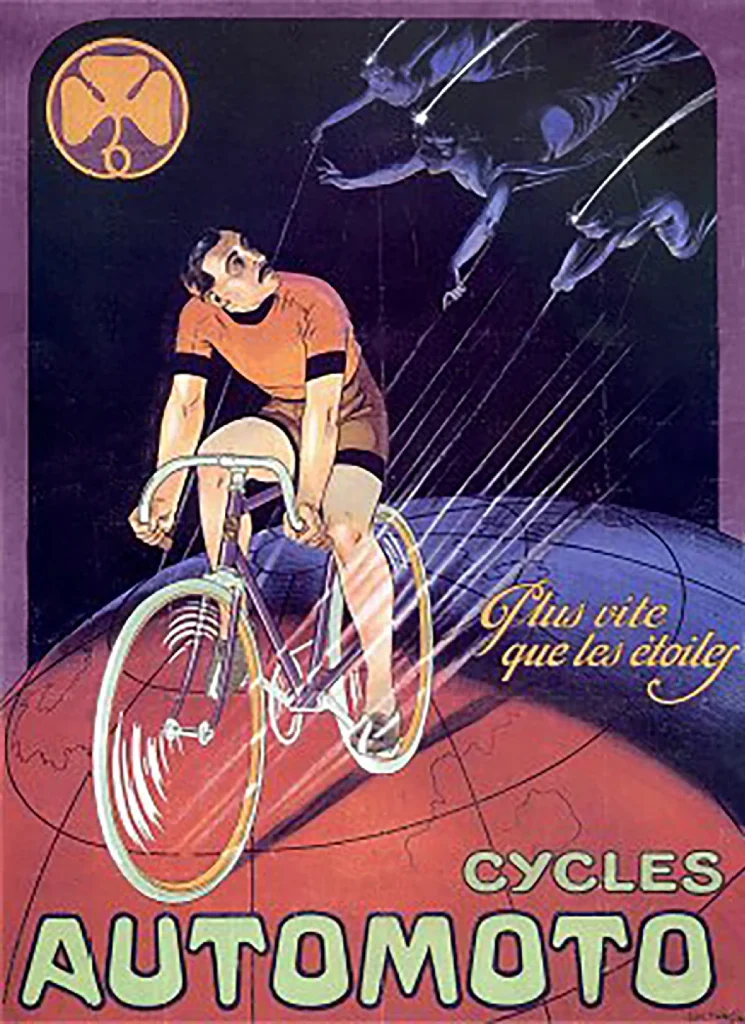

Highly respected among the day’s other great marques such as: Alcyon, Clément, La Française, Gauloise, Hurtu and Peugeot, Automoto bicycles came to become a preferred ride of the racing elite. During a particularly stormy Tour de France in 1913, it was said Lucien Mazan rode “more quickly than the stars” aboard his Automoto racing machine.

The event was memorialized in a popular Automoto postcard featuring the affectionately-known “Petit-Breton” riding swifter than a trailing band of heavenly apparitions. Unable to secure that year’s yellow jersey, the legendary Argentinian cyclist will nonetheless always be remembered as the first to win the Tour de France two times, in 1907 and consecutively when defending in 1908.

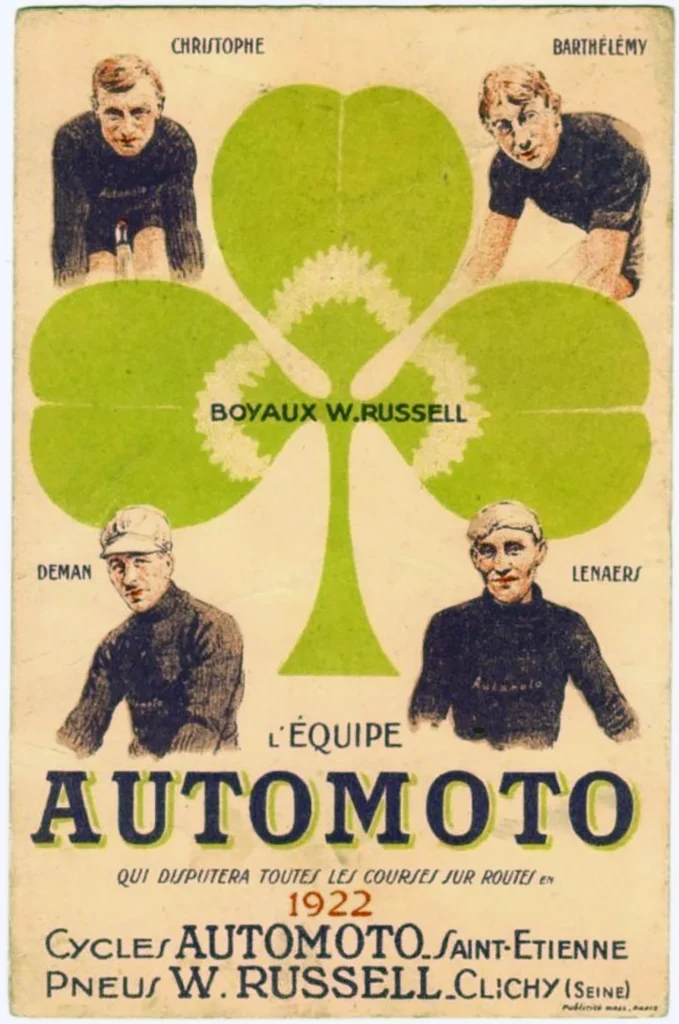

After World War One, Automoto followed a number of prewar bicycle manufacturers and joined the La Sportive consortium in 1919. La Sportive was formed by various French cycling interests confounded by a deep desire to continue professional bicycle racing in the face of abhorred postwar realities and painful economic rebuilding.

Member companies combined resources to equip some half of the peloton under the “La Sportive” name. Cycling author William Fotheringham further suggests the consortium gave constituents the added benefit of controlling riders’ salaries, providing a glimpse into the true motivations behind it for some. Member companies in La Sportive included: Alcyon, Armor, Automoto, Clément, La Française, Gladiator, Griffon, Hurtu, Labor, Liberator, Peugeot and Thomann.

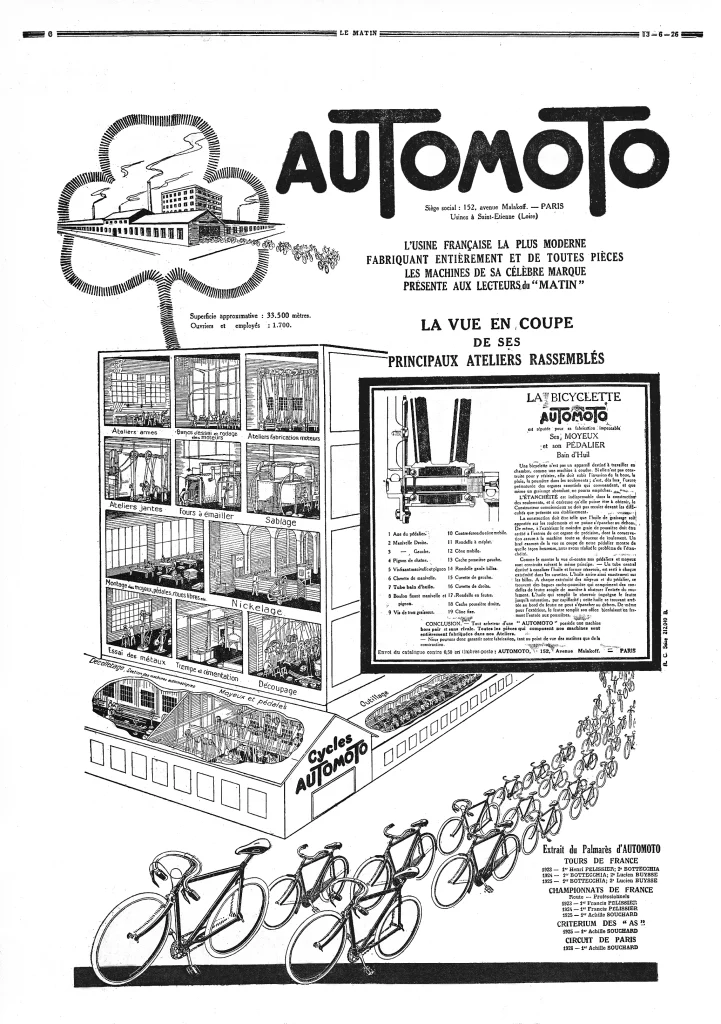

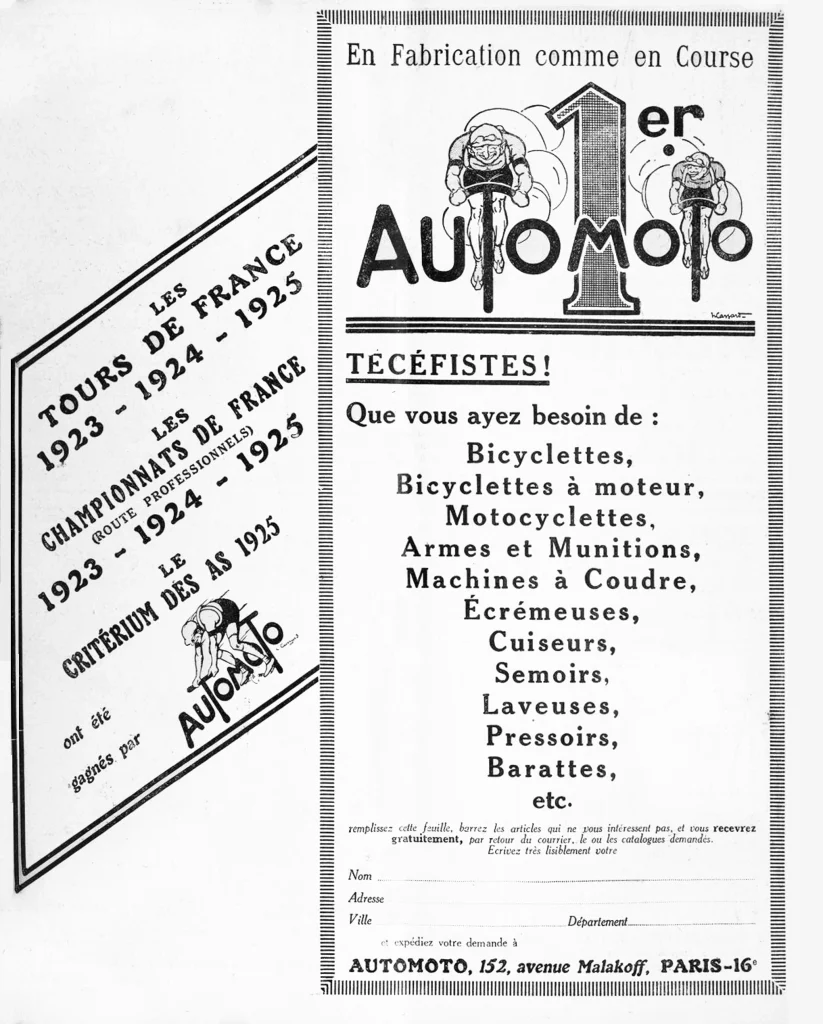

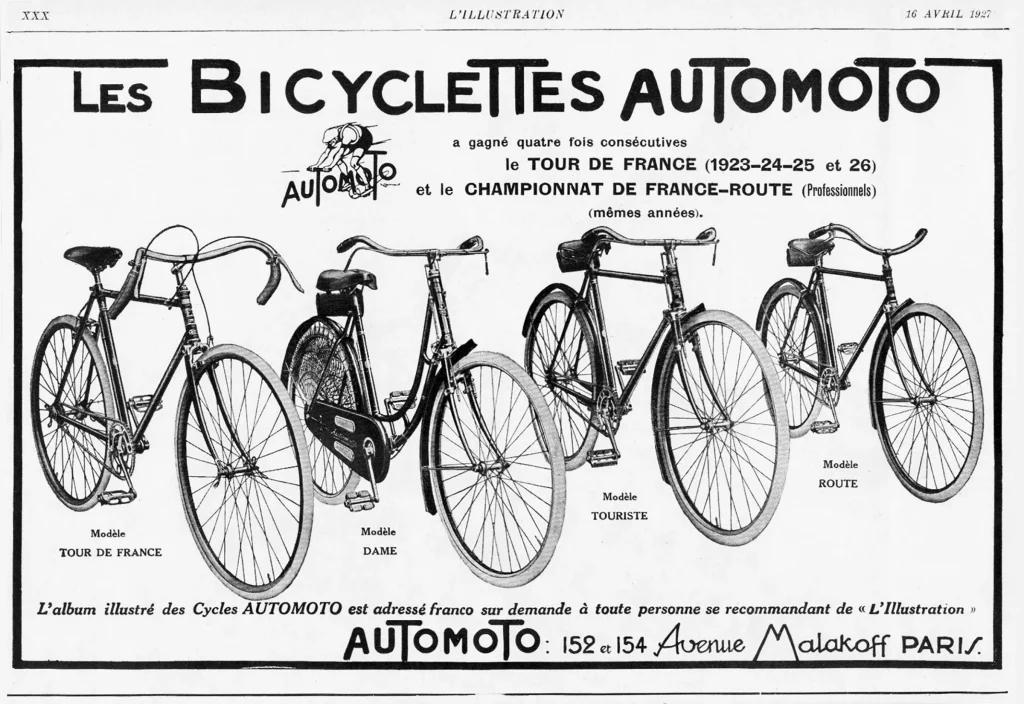

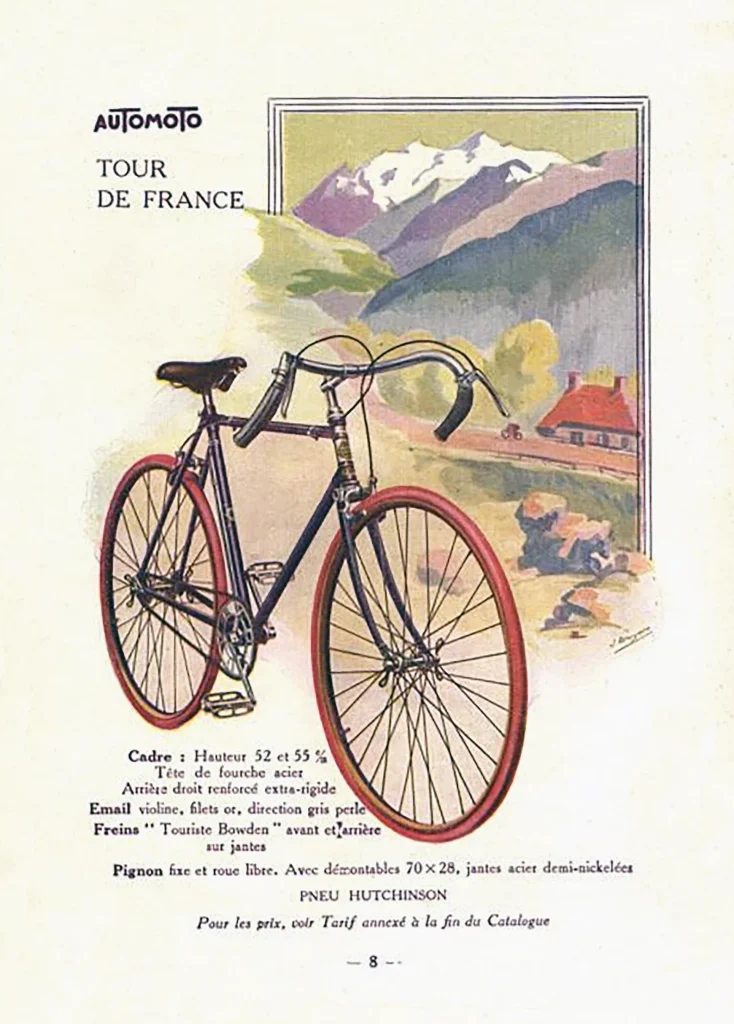

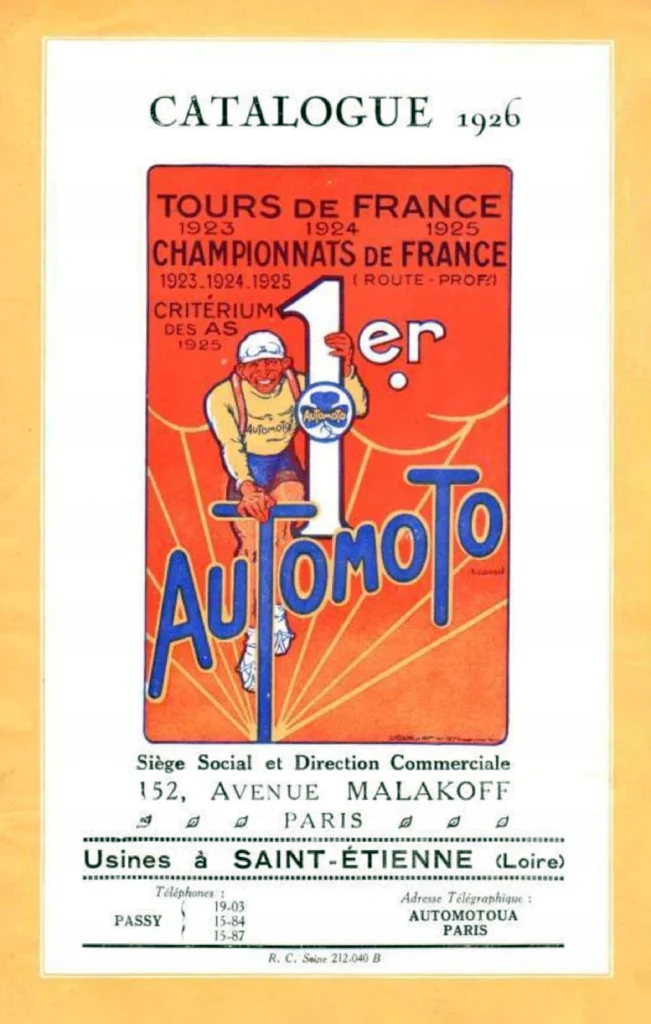

Three arduous years of rebuilding later, several La Sportive members—led by industry titan Peugeot—started promoting their own brands again. Prewar identities newly intact again, Automoto rose to its fullest prominence in the peloton. Its riders dominated professional cycling’s premier event, the Tour de France, from 1923-1926 with a series of convincing victories captained by riders with international appeal like Henri Pellisier (France), Ottavio Bottecchia (Italy) and Lucien Buysse (Belgium).

Another fascinating chapter from the company’s racing heyday was Automoto’s 1926 collaboration with the popular newspaper Le Matin to organize “Les Étoiles de France Cyclistes.” This grand amateur championship involved over 1,000 riders from all across France, culminating in a 199 kilometer finale around Paris. Automoto not only co-organized the event, but provided racing bicycles as top prizes for the individual winners, simultaneously securing its place as the competitive and marketing genius behind the popular enterprise.

Abruptly as the mid-nineteen twenties ended, so did the Automoto winning streak. The summer of 1927 watched a talented Alcyon squad led by several riders from Belgium and Luxembourg establish themselves as the new champion, a label not relinquished until 1930. A label never again coveted by once venerable Automoto, with the standout exception of Fritz Masanek’s unheralded eighteen wins on the Mexican professional cycling circuit in the early 1950s.

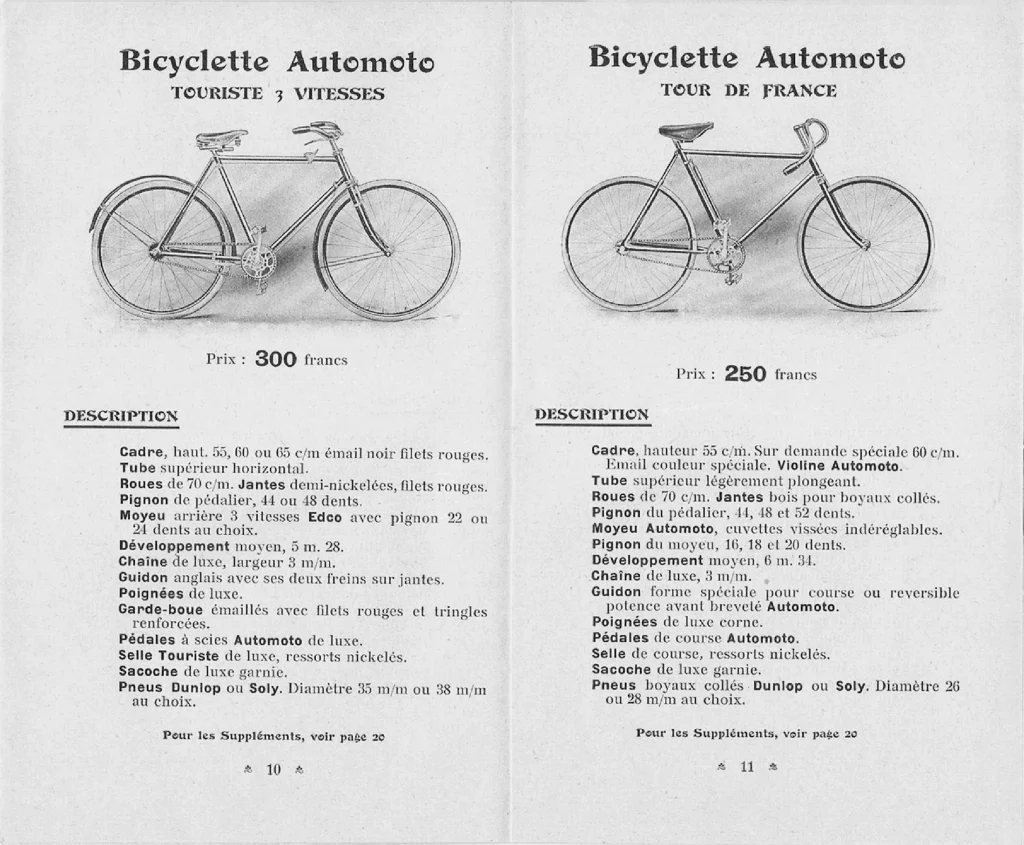

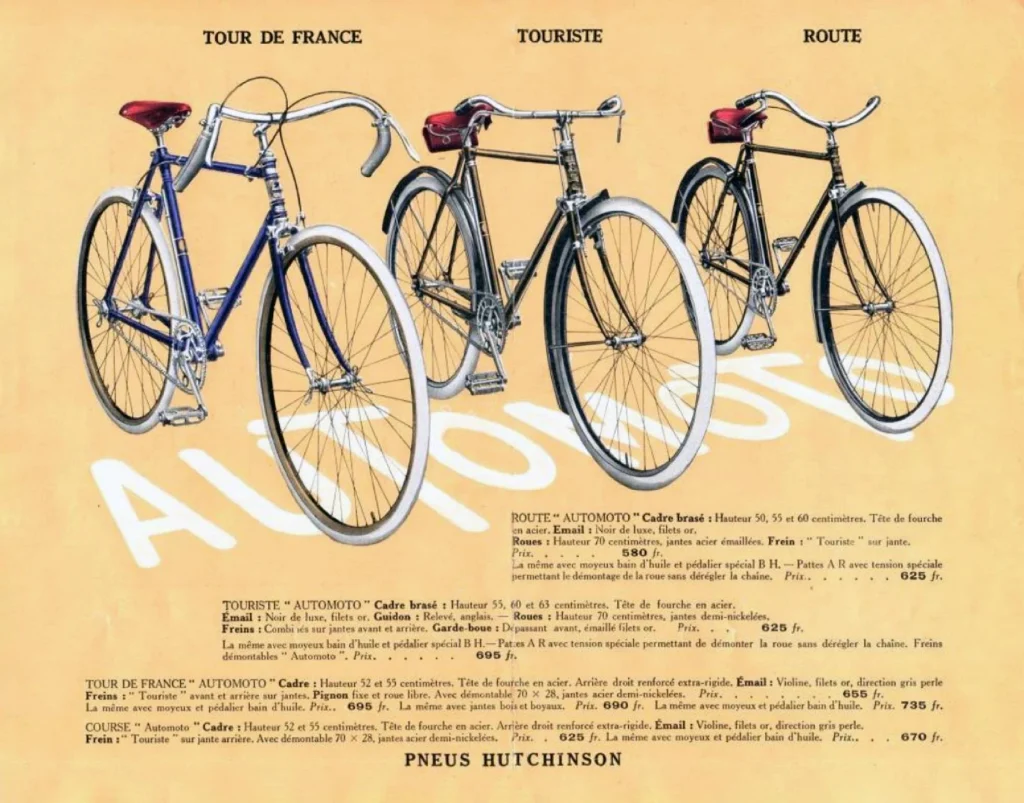

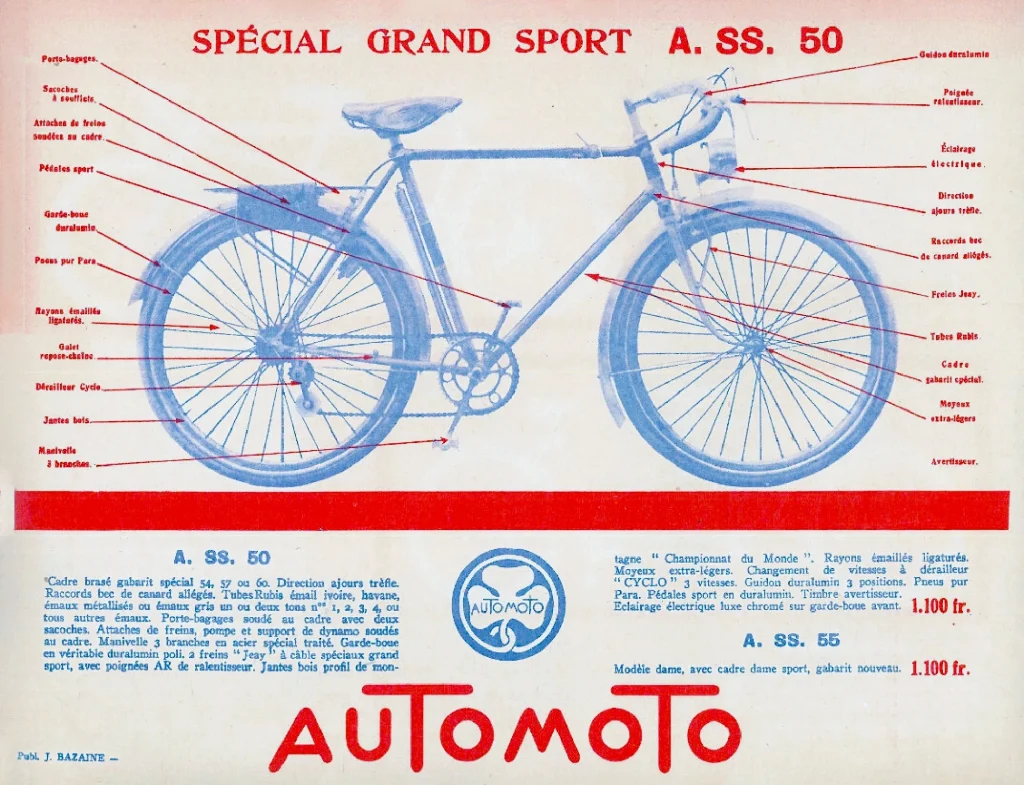

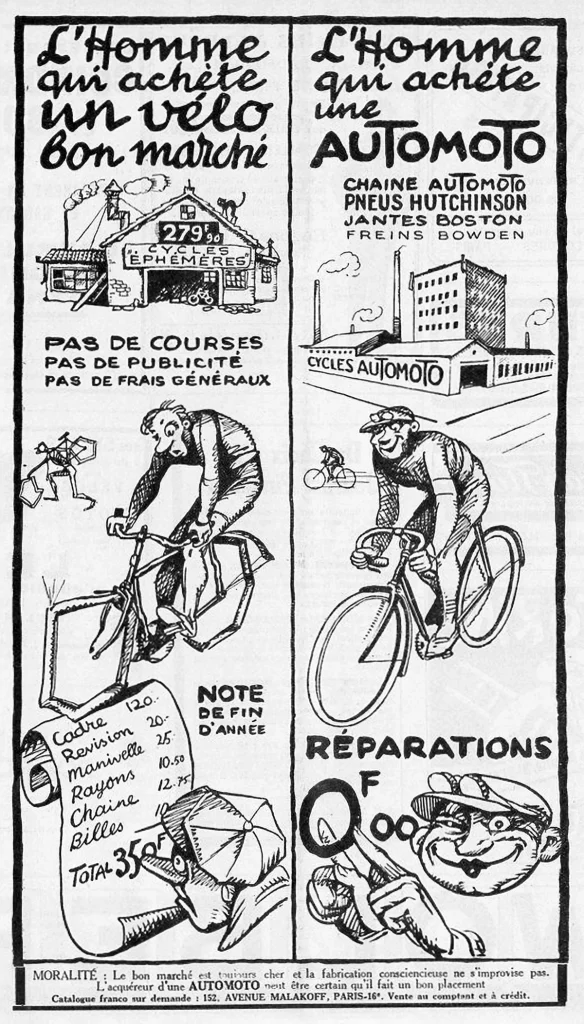

Automoto’s commitment to racing and success on the podium led to decades of loyalty in the marketplace. Its many wins brought increased recognition among competition-conscious buyers and consistently growing sales for the company. Management reinforced the relationship between winning and selling with advertisements featuring competition models alongside others with broader appeal.

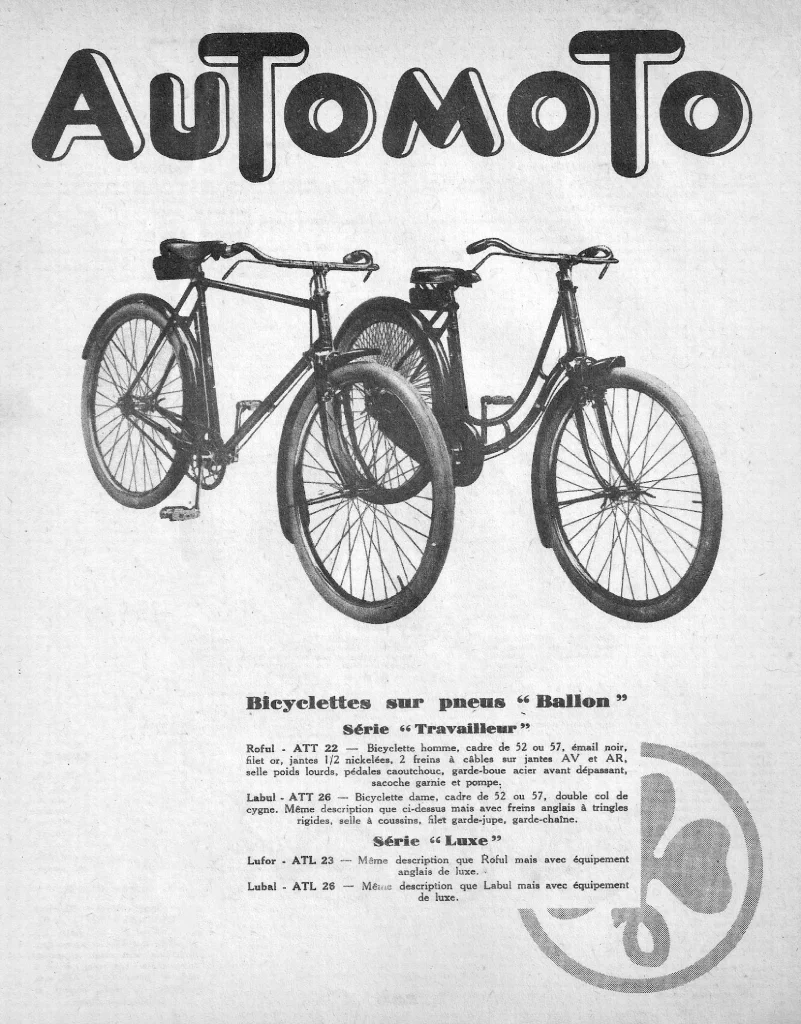

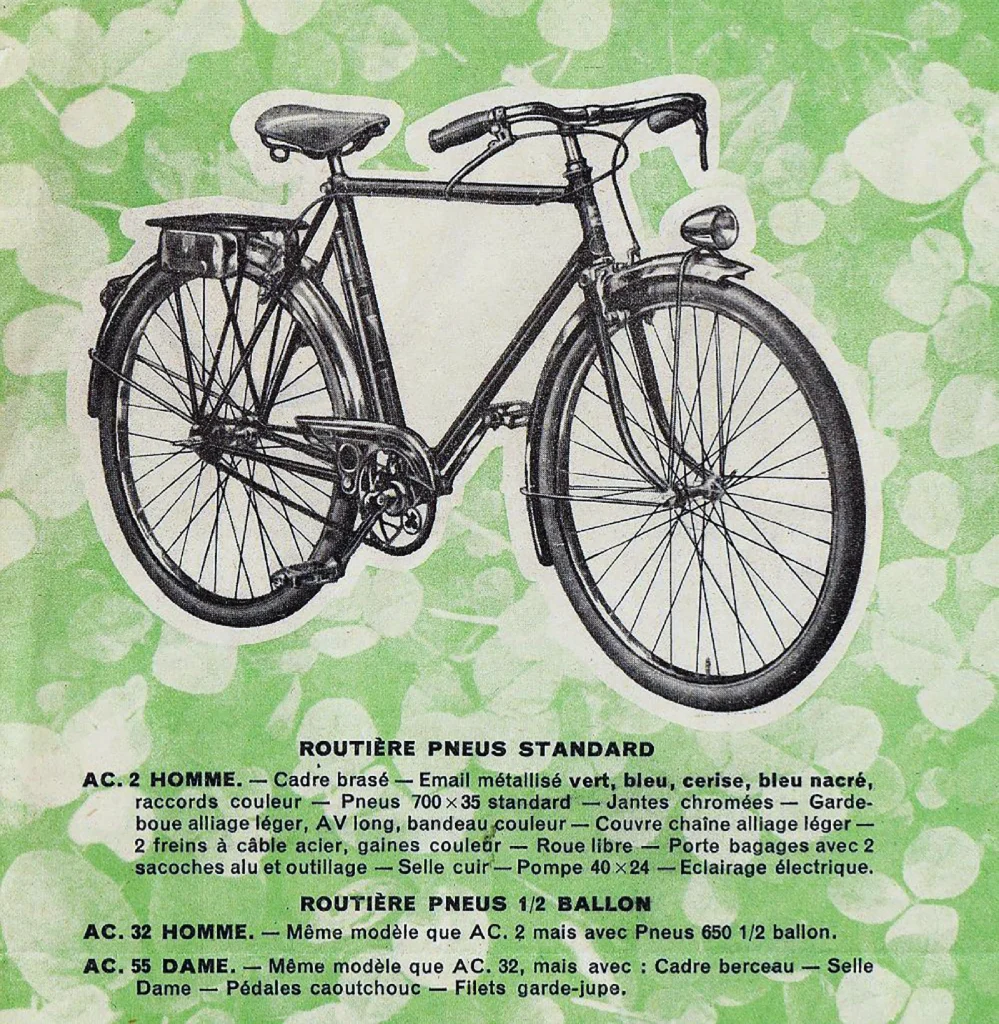

It also responded to emerging demand by expanding the Automoto catalog to include bicycles intended for a variety of applications only then being discovered by the riding public. In as complete an annual Automoto catalog as any on record, 1952 product offerings to the French market included: “grande,” “ballon,” “demi-ballon,” “tourisme,” “randonneur,” “demi-course,” “course” and “porteur” class bicycles, with many available in both men’s and women’s models.

Automoto’s exposure to the U.S. bicycle market seems limited to the early 1950s. Propelled by Masanek’s victories in Mexico, the company began limited distribution of bicycles via Edward Lynch & Son, a mid-twentieth century importer of premium European cycling goods based in Compton, California. The second printing of the Edward Lynch & Son catalog in the early 1950s offered a roundly representative seven Automoto models.

These included: the Deluxe Bicycle touring and racing models in eight speeds, a Fine Lightweight in three speeds, a Quality Lightweight touring and racing models in four speeds, and a Track Racing Model and Deluxe Touring Tandem. Years later, an invoice mailed in May 1957 indicates Automoto directly exported a Professional Light Racer Bicycle (Model ACSP 30) to an individual in Essex, Connecticut. Further details on the importation of Automoto cycles into the U.S. remain murky. An informative pair of reproduction Automoto catalogs are available for purchase online.

The global reach of Automoto extended well beyond its home market and the U.S., fueled by the international prestige of its racing team and a strategic focus on foreign exports. The brand established a significant presence in South America, particularly in Argentina, where exclusive distributors like Dartiguelongue y Toulouse operated out of chic cities like Buenos Aires. This regional connection was bolstered by the fame of the aforementioned Lucien Petit-Breton, the Argentinian national who became the first two-time winner of the Tour de France and was frequently featured in Automoto’s marketing efforts.

Beyond the Americas, the company successfully penetrated various international markets during the early 1950s, with production records highlighting the export of motorcycles to Vietnam in 1951. Morocco also served as a consistent market for the firm’s motorized units, with the company recording multiple motorcycle sales and machine registrations in the country starting way back in 1931. It could be that bicycles were also exported to these markets, though there is no firm evidence to support this possibility. Automoto’s international reach was formalized in 1961 when the marque joined the France Export Association (Frexa), an industrial trade group focused on coordinating and facilitating foreign exports for French manufacturers.

Automoto expanded its market footprint by selling bicycles under an array of sub-brands and associated marques. As early as 1919, the company utilized Christophe as a sub-brand, later adding Jean Louvet by 1927 and Socol by 1955 to its growing commercial portfolio. By 1952, the company’s presence was so broad that it marketed bicycles under various other names, including: Autovélo, Atmos, Violine, Camélia and New Express. This multi-brand strategy (honed by others like Cycles Mercier) allowed the Saint-Étienne manufacturer to saturate different segments of the riding public—from “grande” and “tourisme” models to professional “course” machines—while maintaining the distinct prestige of the primary Automoto brand.

Strategic alliances and industrial collaborations were also foundational to Automoto’s operations, beginning with its 1919 membership in the La Sportive consortium alongside rivals like Peugeot, Alcyon and Hurtu as already noted. Later in the post-World War II era, these partnerships evolved into direct supply agreements. In 1951, for example, Automoto acted as an original equipment manufacturer (OEM) by providing bicycles to Monet Goyon. The company also entered into industrial agreements with other companies like Ravat, and supplied manufacturing machinery to prominent retailers and marques including: Manufrance, Métropole and Rivat Sport.

Automoto’s industrial identity was forged in the “weapon, cycle and ribbon” culture of Saint-Étienne, where the company’s early founders combined a passion for both unpowered and powered transportation. Before 1907, the firm’s output was remarkably diverse, including motorized tricycles, quadricycles and even small “voiturette” automobiles, whose charmingly diminutive size is a favorite among early transportation enthusiasts. However, a forced liquidation in 1907 led the firm to abandon its dedicated car department and focus on the two-wheeled machines that would come to define its legacy. This strategic pivot allowed Automoto to apply advanced metallurgical expertise—originally developed for automobile carburetors and gearboxes—directly to the precision components and high-quality frames made for its elite racing bicycles.

The brand’s expertise in precision engineering was further tested during periods of national conflict, mirroring the industrial versatility of its home city. During World War I, Automoto transitioned to producing military hardware, such as shell fuses, and later manufactured machine guns used on the René Gillet sidecars for the French army. This mastery of military-grade manufacturing somewhat perversely reinforced the “Automoto mystique” – a reputation for “utmost quality and workmanship” that endured for many decades. The company frequently capitalized on this reputation in its marketing, placing professional “course” bicycles alongside its arms and munitions in advertisements to suggest the same rigorous standards of reliability applied to both lines of business. How clever and sickening at the same time, mixing the sacred and horrific like that purely for financial gain.

Beyond motorized and military goods, Automoto became a staple of the French household through an expansive catalog that included: sewing machines, washing machines, cream separators and even furniture. By 1952, the brand offered a massive array of products to the French market, ensuring the iconic cloverleaf logo was a ubiquitous symbol of French quality in both the home and peloton. This broad manufacturing footprint supported the bicycle division by maintaining a high degree of brand loyalty and visibility. A cyclist might trust an Automoto “grand luxe” bicycle precisely because the brand’s engineering was already proven in their family’s sewing machines and agricultural equipment. See, no killing was needed to sell bikes after all.

The Cycles Automoto legacy ended abruptly in 1959 when Indénor—a subsidiary of Peugeot—purchased the Automoto brand rather unceremoniously and ceased production soon thereafter, further monopolizing previously overlapping lines of business. Only a decade earlier, when an Automoto advertisement boldly declared, “Le Triomphe De La Qualite Française,” few in sound conscience would have doubted the claim. Such is the nature of the bicycle business, fickle and merciless as it can be.

Half a century removed from the politics and persuasions of the day, the Automoto mystique—that of utmost quality and workmanship—endures today. Even as fewer examples of Automoto bicycles exist, and those that remain command unprecedented premiums in the marketplace, the company’s commercial artwork is enjoying renewed appreciation among urbanites and vintage bicycle enthusiasts alike. Enlightening, in an era where the TGV hustles legions of passengers from Paris to Saint-Étienne in under three air-conditioned and air-cushioned hours many times daily.

Lucky collectors of Automoto bicycles especially appreciate the sculpted clover lugwork found on fancier frames and trademark fork crowns. Mated to long rake fork blades, the stylized square crown with clover coin inserts was “purposely designed so as to withstand the most violent efforts, especially braking strain, and suppress all vibrations,” according to 1957 company literature. It should come as no surprise that the design achieves these objectives remarkably well for a passive suspension package conceived over 100 years ago. After all, that is the Automoto way.

Perhaps those early constructeurs back in Saint-Étienne were onto something. Their long hours spent drawing tubes by the fire, their dedication to understanding the geometry of champions, their jarred bones suffered from cobblestone field tests, none of it was for naught. The Automoto spirit continues living deep in many of us and forever will. With a dash of good luck, anything is possible.

http://tontonvelo.com/Automoto_Eng.htm

http://www.cybermotorcycle.com/euro/brands/automoto.htm

http://www.sheldonbrown.com/velos.html

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saint-Etienne

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lucien_Petit-Breton

https://www.bikeraceinfo.com/tdf/tdfindex.html

http://www.theracingbicycle.com/Early_History.html

http://www.velo-retro.com/list.html

[…] Cycles Automoto: Setting the Standard – https://www.ebykr.com/cycles-automoto-setting-the-standard/ […]

[…] Cycles Automoto: Setting the Standard […]

Story of the man who sold it to me was that it was owned by Lucien Mazan winner of the Tour that lived here in Argentina

I have an Automoto w/Simplex. Don’ yet know exactly model/year. Can you help?

I own a1928 automoto. A8 it’s a 175cc two stroke. Two speed in running order it has been professionally restored. At great expense the bike completed the banbury run some years ago. It is thought to be the only one in the U.K. Brian inman

[…] Cycles Automoto: Setting the Standard […]

[…] of motorcycles continued until stocks at another Peugeot subsidiary — the venerable Automoto — were depleted in 1961. Lingering market demand compelled Peugeot to continue building […]

Some antique collectors just have a passion for history. They like to be familiar with and to know why an individual object was used, how ıt had been used or who applied it. They are interested by the obvious ways which the world and technology possesses changed and grown. By collecting objects on the past they feel like they are partially connected to a period in which they for no reason lived, is long gone but somehow still survived.

I have in Pordenone(Italy)an Automoto original from Ottavio Bottecchia winner of tour France 1924.

A great bike!

For Bob Sirkus or any other indivudual interested in restoring an Automoto bike. I found a bicyle restoration company in Vista California called Cycle Art. They have the orignal art required to restore an Automoto on file and professionally redid my Automoto. It looks great!.

Question, did CyclArt really have artwork on file for an AutoMoto? Thanks, K. Johnson

My parents bought me a 20″ Automoto model in 1955. I still have the picture of me proudly holding it up in front of the Christmas tree. Other kids in the Bronx NYC got Shwinns or Huffy’s but none could catch me on a long uphill climbs that make up the Bronx. Light durable and speedy it made me admire things French. It was one of the reasons I studied French in High School. I cared for the bike well and never forgot the name. One day I just tried a search and was shocked to see the green frame and red tires I had raced on appear on your website. Thanks for the connection..

I have also just come across an AutoMoto 3 speed, no wheels or seat.

Very light & graceful lines. Unfortunately seat stays detached

from frame due to rust. Any tips how to re-attach without brazing or weld. (shop wants $90 to look at it!)

Brake levers have plastic shrouds.

I found what i suspect to be an early 60’s automoto 3 speed in very good condition for its age. Having alot of trouble finding out info on bike. It’s the first time even ebay couldnt gimme an idea of value, all they have is a poster of it. If you find any helpful sites let me know please.

i have a late ’50s Automoto 3 speed which was my bike as a teenager. i would like to get it restored. can anyone provide information on where to find parts?

I have an Auto Moto bicycle from the early 1960’s. It was given to me by

a French professional bicyclist who stayed at our home in West Hartford,

CT. He was touring the US promoting the Tour de France

I recently purchase an old bicycle and am hoping to locate some information on it. Listed below are the details. Can you offer any information you may have about it?

Thanks

blue with yellow painted letters and labels

lugged

Reynolds 851

a long series of numbers and Nervex stamped in bottom of bottom bracket

“La Sportive” in large letters on the down tube

“Paris” on the seat tube

one Huret downtube shifter for the rear 5 speed cluster

no shifter or deraileur for the front 2 rings

smaller front ring on the outside closest to pedal

Wind double bolt stem

I seem to be at a dead end collecting information. Any help would be appreciated.

Thanks

[…] In 1960 Terrot was unceremoniously absorbed into the Indénor subsidiary of Peugeot. Assembly of motorcycles continued until stocks at another Peugeot subsidiary – Automoto – were depleted in 1961. Lingering market demand compelled Peugeot to continue building general purpose bicycles under the Terrot name until 1970. […]