About Ebykr

Ebykr celebrates classic and vintage lightweight bicycles through provoking imagery and opinion. Let's roll together!

About Ebykr

Ebykr celebrates classic and vintage lightweight bicycles through provoking imagery and opinion. Let's roll together!

Introducing MAFAC

In the historical archive of classic lightweight and vintage bicycles, some components get relegated to lowly footnote status, while others stand tall as towering monuments to engineering achievement. Among the latter, the name MAFAC—an acronym derived from the elegant French moniker, Manufacture Arvernoise de Freins et Accessoires pour Cycles—dominates the ongoing conversation about brakes and braking.

Founded in the city and commune of Clermont-Ferrand in post-war France, the company transcended basic manufacturing to deliver elegance, versatility and sheer stopping power to burgeoning cyclists when they needed it most: while going too fast, often down steep mountain grades on rickety old bikes overloaded with luggage or goods. Indeed, some cycling historians proclaim MAFAC produced, “the first brakes that actually worked.” And worked they did, with the company’s racy Top-63 model tested at 60 m.p.h. under load, as proclaimed in a bold advertisement from 1964.

MAFAC’s innovations shattered the pre-existing mentality, exemplified by some of its competitors, that the purpose of a bicycle brake was not to stop, but to decelerate. While French manufacturers were responsible for several notable “faux pas”—like the fragile Delrin plastic Simplex derailleurs or the notorious AVA “death” stem—the original MAFAC Racers were universally regarded as magnifique. Their obvious excellence catapulted the company to overnight success and allowed it to reign supreme for two decades until bigger, arguably better alternatives started eating away at their core market share. Two decades after that, they were gone altogether. Come learn about all the juicy bike history that happened in between…

Another Racer Turned Maker

MAFAC was founded by Auguste Bourdel in 1946. Born in 1894 and raised in the Clermont-Ferrand area, Bourdel had been a professional bicycle racer in his mid-20s, when his love for the sport must have been nurtured accordingly. As this love evolved into his middle years, Bourdel started producing bicycles of his own making (or at least name) that achieved a considerable degree of commercial success, judging by the admittedly-thin historical record and remaining few specimens available. Included here were mixte-style machines for the ladies, double diamond machines for the men, and tandems for them both.

Bourdel bicycles were and are renowned for their finish and quality, with their connection to MAFAC and relative obscurity enduring legacies of the brand. The few Bourdel examples remaining today feature a couple of interesting characteristics:

Headtube badges on Bourdel bicycles depict the Puy-de-Dôme mountain, Clermont-Ferrand Cathedral and two factory chimneys, likely those of the Michelin factory that MAFAC itself would come to occupy a few short years after Bourdel started producing bicycles nearby. Perhaps this was a premonition of the decreasing relevance of Bourdel bicycles, or of the increasing relevance of MAFAC brakes. Either way, it would become glaringly obvious which brand ascended to the pantheon of the sport, with few remembering Bourdel bicycles today and many still stopping on MAFAC Criterium or Racer brakes a full 40 years after the company ceased operations.

Despite dedicating himself to his industrial interests around 1920, Auguste Bourdel hardly limited himself to just bicycle building. He established, among other things, the Grimpée Cyclotouristique du Puy-de-Dôme in 1946 and the Poly d’Auvergne in 1952, two mid-century cycling events widely attended by countless cyclotouristes. Nor did Bourdel confine himself to just event organization. Never content to coast for too long, he also participated in these events himself and held the best time in his category at the Grimpée for over 50 years and may still today. (Jo Routens also comes to mind in this context, who both built and rode in a big way himself.)

Making Papa Proud, Posthumously

Upon Auguste Bourdel’s untimely death in June of 1954 at age 63, Bourdel’s daughter, Mme. Mazen-Bourdel, played a pivotal role in advancing the company forward. It has been documented that she grew the company’s sales and modernized its industrial capacity for several years after her father’s passing, always maintaining the MAFAC brand’s unwavering commitment to quality over price. This outlook unironically led to further prosperity for the company, allowing it to expand its ever-better machinery, installations and methods used on the factory floor, eventually under the stewardship of manager Paul Bertrand starting in 1958.

Mme. Mazen-Bourdel’s efforts here included new industrial drills, milling machines, riveters, cutting presses and tooling for bicycle, cyclo and car parts. They also led to new polishing, cadmium plating, zinc plating and bright nickel plating installations. Most importantly, the introduction of strict thermal controls in the company’s manufacturing processes guaranteed the robustness of its aluminum and steel products, a key advancement that unlocked product design opportunities for years. The Bourdel family continued to benefit from their gifted daughter’s insights and managerial skills until her own untimely death in 1960, the cause of which was a road accident in the family’s hometown of Clermont-Ferrand.

From Securité to State-of-the-Art

The MAFAC brand and products that we know and love actually began under the initial corporate name “Securité,” a logical choice reflecting the crucial mission of making cycling safer in a world where braking often meant putting one’s life in their own hands, literally sometimes. One very early, turn of the 20th century braking design relied on riders using a thick, mitt-like glove (usually worn on the dominant side) for grabbing the front wheel from above and pressing on/squeezing it until the bike slowed down. Yes, as though your trusty hockey glove was a bicycle brake pad and your hand was a combined spoon brake and caliper. Clearly, vividly, the opportunity for technical advancement was wide open to any and all comers. And so the void was filled, one braking innovation and countless averted accidents at a time.

The company’s initial product line established its reputation instantly, focusing on three core products marketed under the “Securité” marque: cantilever brakes, brake levers and tool kits. The cantilever brake, introduced in 1946, was a foundational triumph. Compared to its predecessors, the design was more powerful and easier to set up and use. Known models included Kathy, Driver and Criterium. The Criterium series remained in production for about four decades. This brake type was specified on nearly every lightweight tandem, high-quality and fully-loaded touring bikes, and most cyclo-cross racers. Crucially, the cantilever design, which was attached by pivots on the frame and fork, helped clear the axle hole on the fork crown and freed it up for other practical accessories like a front rack and/or light.

The Securité company officially transitioned to the MAFAC name in the autumn of 1947 and applied for a trademark shortly after. The aforementioned factory was established at the former Michelin workshop at 25, Rue d’Estaing in Clermont-Ferrand. Anchored in the Auvergne region in central France, the stage was set for decades of success. MAFAC would become an important contributor to establishing the Clermont-Ferrand – Saint-Étienne axis as the first epicentrum of the French cyclo-tourist industry. (Today, that crown likely belongs to La Vélodyssée/EuroVelo 1, whose 1,200km route runs along the Atlantic Coast from Brittany to the Basque Country and generates over €100M in annual economic impact. One can easily see why: more water, fewer hills.)

Renowned mid-century L’Equipe journalist Claude Tillet wrote that, “M.A.F.A.C. won the battle of the cantilever, thus summarizing the result of hard work, the fruit of experience and the will of a man whose conception was constantly striving towards better.” Amen, brother Claude.

The Center-Pull Zenith: Le Racer

MAFAC’s undisputed magnum opus (sorry, Hetchins) was unveiled in 1952 at the Paris bike show. This brake was hailed as the first effective center-pull design, marking a fabulous advance over the notoriously ineffective side-pulls of the period. The power was so profound that MAFAC boldly promoted the brakes with the slogan: “Un doigt suffit!” – “Braking with one finger is enough,” or quite literally, “One digit suffices.”:

The key to the MAFAC Racer’s superiority lay in both its construction and clearance:

MAFAC’s lead as an innovator was substantial. Major rivals like Weinmann of Switzerland and Universal of Italy failed to release their own center-pull models until the late 1950s and early 1960s respectively, nearly 10 years after MAFAC first introduced the Racer.

Form, Function and Flamboyance

The Mafac Racer was the company’s highest-volume product, produced with little alteration from its 1952 debut until the early 1980s. It boasted a “curvy, alluring shape that was pure Gallic.” The engraved MAFAC logo and the word Racer in double speech marks gave it a memorable nickname and flamboyant look. This aesthetic was often enhanced by red bushings that framed the script on the 1970s iteration.

The MAFAC Racer was a masterpiece of versatility and adjustability:

Before Campagnolo’s first Record caliper arrived in 1968, Mafac Racers were a common sight in the pro peloton. The Racer’s compact profile made it the caliper of choice for all mid-century, equipment fanatic, time triallist types. Professional riders like five-time Tour de France winner Jacques Anquetil favored them. Bicycles equipped with MAFAC brakes are credited with winning more Tours de France than any other brand in the 20th century, except of course unrivaled Campagnolo.

The only persistent criticism of MAFAC’s Racer brakes were their acoustic tendency: they were prone to loud and annoying squealing, making one’s approach to a corner or descent down a hill “a sound much more alarming than it actually was.” All in all, most of us would probably sacrifice some level of annoyance for absolute safety. One need look no further than MAFAC’s success in the marketplace for validation here.

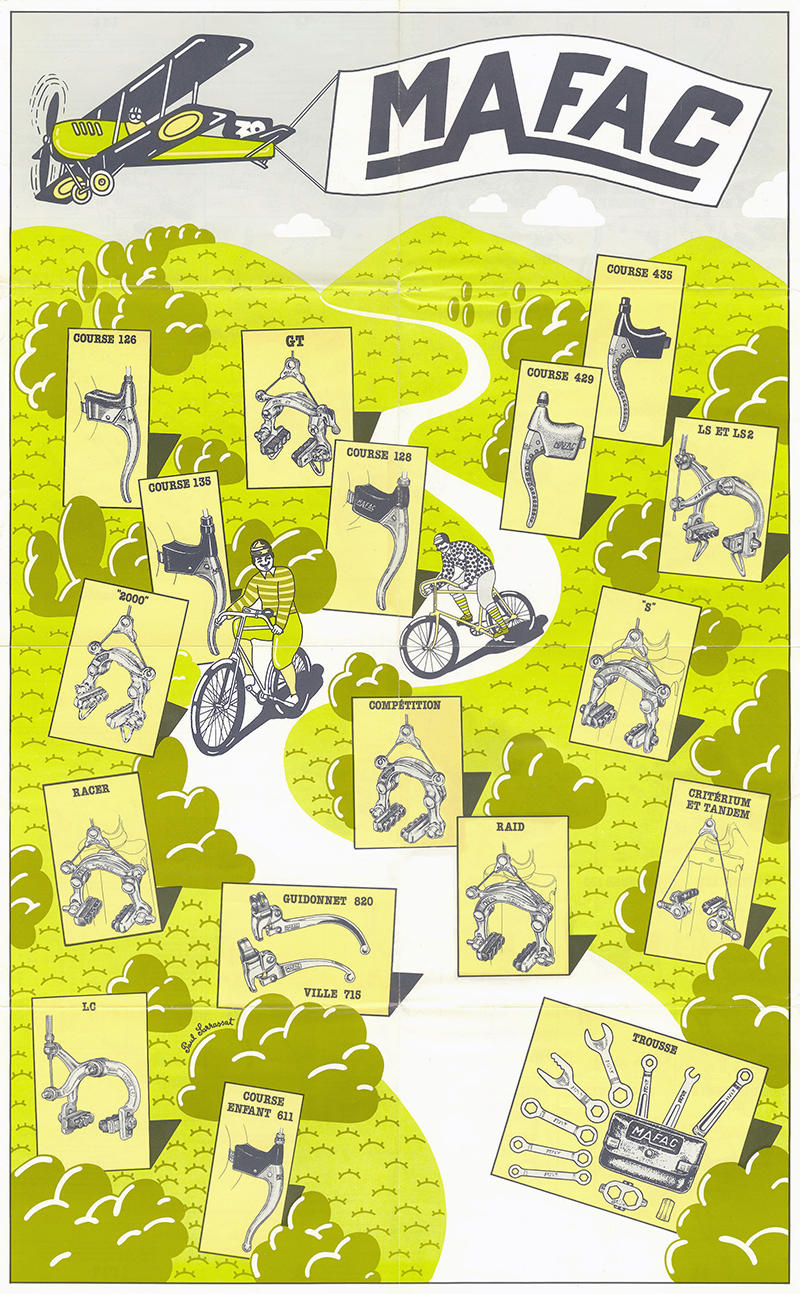

The Full Lineup: From Competition to Collectors’ Rarities

While the Racer reigned supreme, MAFAC developed several other center-pull models:

MAFAC also developed the studded brake block (or brake pad), a highly durable and effective component, which influenced future component construction and notably wore out rims less severely than previous whole-block designs. Three blocks for racers, four blocks for cyclos and five blocks for tandems and motos.

The Genius of Levers and Tool Kits

MAFAC’s accessory line was as functional and stylish as their calipers. Their brake levers evolved from all-aluminum bodies with solid blades to later versions featuring resin bodies and drilled lever arms for weight savings. Specific lever types included Poignées ville (city levers), guidonnet (handlebar levers), course (racing levers) and poignée inversée (inverted levers, like those used on period porteurs). Mafac 2000 levers from the 1970s were offered in both drilled and smooth versions, including highly coveted gold-anodized finishes. Super trick on both counts.

The company’s crowning accessory innovation, however, were those rubber brake hoods that originated in the late 1940s. The hoods featured built-in barrel adjusters, an ingenious addition that allowed riders to fine-tune their brake pad clearance without leaving the handlebars. Associated levers were cleverly designed to allow the hood to be removed quickly without needing to un-tape the bars. The hoods were available in half-hoods or full-hoods and came in a veritable rainbow of colors: black, tan, white, red, green and blue. New translucent rubber covers were introduced later, offering greater suppleness and an improved cable tension adjuster. How fun and very high margin.

Recognizing that every serious cyclist needed to be self-sufficient, MAFAC manufactured, marketed and sold comprehensive tool kits for general repair. These kits, sold in metal tins, cloth sacks, leather pouches and then injection molded, plastic envelope-type bags were designed to hang from the back of the saddle or straddle across the seat tubes above one’s fenders, at least those marketed to cyclists and not motorcyclists. They contained the specific tools necessary for adjusting MAFAC brakes, and performing other roadside bicycle adjustments and repairs. Tool kit models included: the Mod. 44 (five tools), Mod. 45 Constructor (six tools), Mod. 46 Touriste (seven tools) and Mod. 48 Randonneur (10 tools). Each model featured certain two-sided tools to increase their functionality. The fullest Mod. 48 Randonneur kit even included a pedal spanner, cone spanner and spoke spanner.

The Art of Engineering: Daniel Rebour and the Illustrated Blueprint

While MAFAC engineers mastered the function of braking and its accessories, the brand’s enduring prestige was elevated by the beauty and precision of its technical documentation, largely thanks to legendary cycling illustrator, Daniel Rebour. Rebour’s imprint on MAFAC publications, such as the 1978 MAFAC catalog, ensured that the technical superiority of the company’s components was matched by visual clarity. His signature style, featuring meticulously detailed cut-away views and exploded diagrams, was indispensable for presenting components like MAFAC’s highly complex, multi-adjustable brake calipers and the inner workings of its levers. Rebour’s illustrations transformed mechanical assemblies into easily understood blueprints, offering mechanics, enthusiasts and collectors an unparalleled window into the fabulous engineering that MAFAC represented beginning on day one.

End of an Era

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, MAFAC attempted to adapt to new trends by producing side-pull brakes concurrently with their core center-pull and cantilever lines. These included the angular LS model and the later LS2, which resembled Campagnolo Nuovo Records. A mid-range brake set named LC was also offered in side-pull configuration. Unfortunately, this side-pull series (LC, LS, LSX and LS2) eventually suffered from widespread reliability problems, which contributed to the company’s growing misfortune and diminishing relevance.

To compete with growing Japanese (think Shimano and Suntour) and Italian (think Campagnolo) dominance, MAFAC joined a French component partnership known as the Spidel consortium, providing calipers and levers (including the Competition and MAFAC 2000 models). Other members included: Maillard, Simplex and Stronglight. Despite these efforts, economic pressures and strong competition from groupset manufacturers ultimately led to MAFAC’s ceasing operations in 1985 and disappearing altogether in the late 1980s. Some of the company’s assets were sold to ACS, the U.S. maker of super rad BMX-related products like those killer Z Rims the fortunate few among us rode as kids, present party excluded, enviously.

Enduring Legacy

Despite their fuzzy demise in the late 1980s, the MAFAC legacy endures today in at least two distinct ways:

Original MAFAC components remain lightweight and extremely reliable. Many are still in use today, on bicycles regularly seen around town, here, there and everywhere. For those maintaining or upgrading vintage cycling machines, especially in the popular 650B and 700c wheel sizes, knowing the company’s product identification stamps can be helpful when sourcing period-correct parts:

Parting Thoughts

MAFAC’s legacy is defined by overcoming the audacious engineering challenges stemming from the simple belief that cyclists deserved “the first brakes that actually worked.” The company broke through the competitive philosophy that the purpose of a brake was merely to “decelerate,” replacing timid, poor-stopping side-pulls—like the famously nicknamed Universal 68 “courtesy brake”—with dural-forged stopping power. This technical breakthrough, enabling “one-finger braking,” solved the twin problems of powerful stopping and superior clearance, a necessity for touring bikes and other fatter-tire and/or fender types.

The genius of the center-pull and cantilever designs was so inherently robust that they became foundational blueprints, influencing later systems like those produced by Dia-Compe and Shimano, and their engineering principles remain current by modern manufacturing standards. This is the highest compliment any bicycle component can receive: longevity not just in operability, but in design philosophy.

MAFAC delivered the essential promise of cycling safety with Gallic flair, earning its place on machines ridden by champions like five-time Tour de France winner Jacques Anquetil and those built by pioneers like Mike Sinyard, founder of Specialized Bicycle Components. Its pioneering Competition and legendary Racer models may have left the production lines decades ago, but their perfect geometry will always stop our hearts.

Le Racer est mort, vive le Racer!

Ebykr Article Sources

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mafac

https://www.flickr.com/photos/mafac_brakes/

https://www.cyclingweekly.com/news/latest-news/icons-of-cycling-mafac-racer-brakes-206323

https://sscycleworks.com/components/brakes-mafac.html

https://www.sl-sport-equipments.com/gb/br-237-mafac

https://www.velo-pages.com/main.php?g2_itemId=44567

https://midlifecycling.blogspot.com/2014/10/the-first-brakes-that-worked.html

http://cyclespeugeot.web.fc2.com/reminiscence/mafac78.htm

https://www.velovintageagogo.com/t14374-mafac-son-histoire

https://forum.tontonvelo.com/download/file.php?id=401503

https://forum.tontonvelo.com/download/file.php?id=401502

http://cyclespeugeot.web.fc2.com/reminiscence/mafac78.htm

https://bikeville.net/2015/10/13/mafac-acs-cantilever-brakes/

https://mbaction.com/the-history-of-the-stumpjumper_updated12-24-22